Documenting the Spread of Developmental Education Reform

By Dominique Dukes

Developmental education has changed significantly in recent years. Traditionally, most students’ college readiness was assessed using a standardized test such as COMPASS (now discontinued) or ACCUPLACER. Students who scored below a prespecified cutoff would be referred to a developmental education course or course sequence designed to prepare them for college-level coursework in math, reading, or writing. Many students would be assigned to two or three semesters of developmental coursework before they could enter college-level courses.

However, as a growing body of research has called into question the effectiveness of these traditional practices, colleges and college systems across the United States have been experimenting with different approaches to developmental education.

In 2016, CAPR fielded a survey about developmental education practices to a nationally representative, random sample of 1,055 broad-access two-year and four-year institutions (those admitting 70% or more of applicants). The survey was designed to identify assessment, placement, and instructional practices used by colleges in developmental math, reading, and writing for the 2015–16 academic year. Additionally, CAPR interviewed 127 college faculty and leaders from 83 public colleges, college systems, and state-level higher education governing bodies.

Today, CAPR published a report that summarizes the full scope of these data, providing the first nationally representative picture of developmental education since 2011. Here are some highlights from the report.

Most broad-access public colleges assess students’ college readiness and offer developmental education courses to students identified as underprepared for college-level coursework.

Virtually all public colleges assess students’ college readiness, and most (99% of community colleges and about 83% of four-year colleges) offer developmental education courses. Public colleges tend to offer many more sections of developmental math than developmental reading and writing. Furthermore, community colleges offer over twice as many sections of developmental math and English than do public four-year colleges, despite both types of institutions being similarly sized on average.

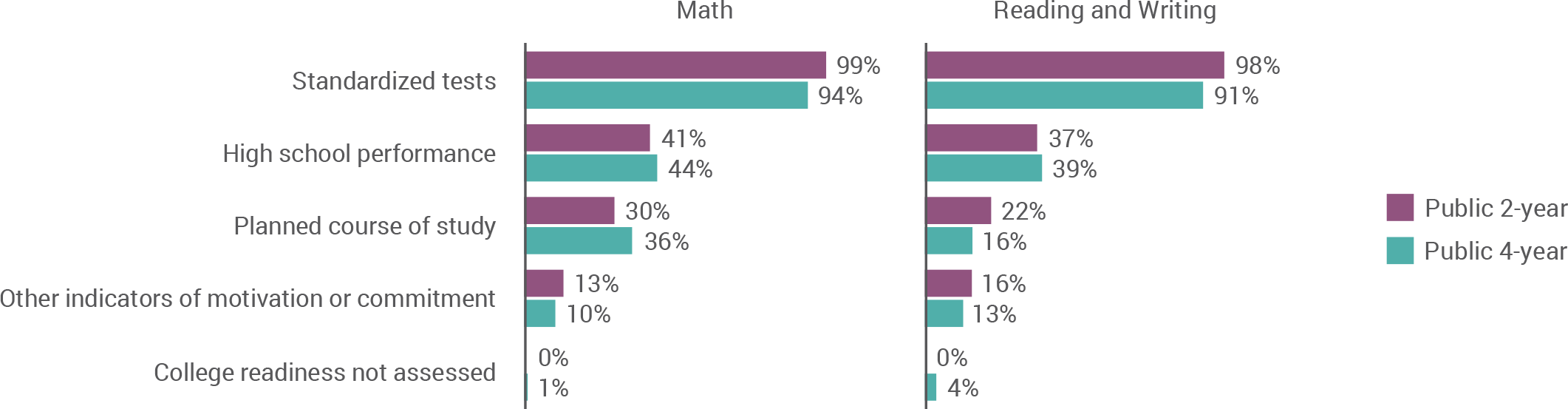

Most colleges rely on standardized tests to assess college readiness, but a growing number of public colleges are using additional measures.

Over 95% of public colleges still administer standardized assessments, but over two thirds use at least two measures to guide placement—a 30-percentage-point increase from 2011, when less than 30% used any measure other than standardized test scores for placement. Two of the most common alternative placement criteria used are students’ high school performance (including GPA, grades in specific courses, or high school exit exams) and intended major.

Processes Used to Determine College Readiness Among Public Colleges, Academic Year 2015–16

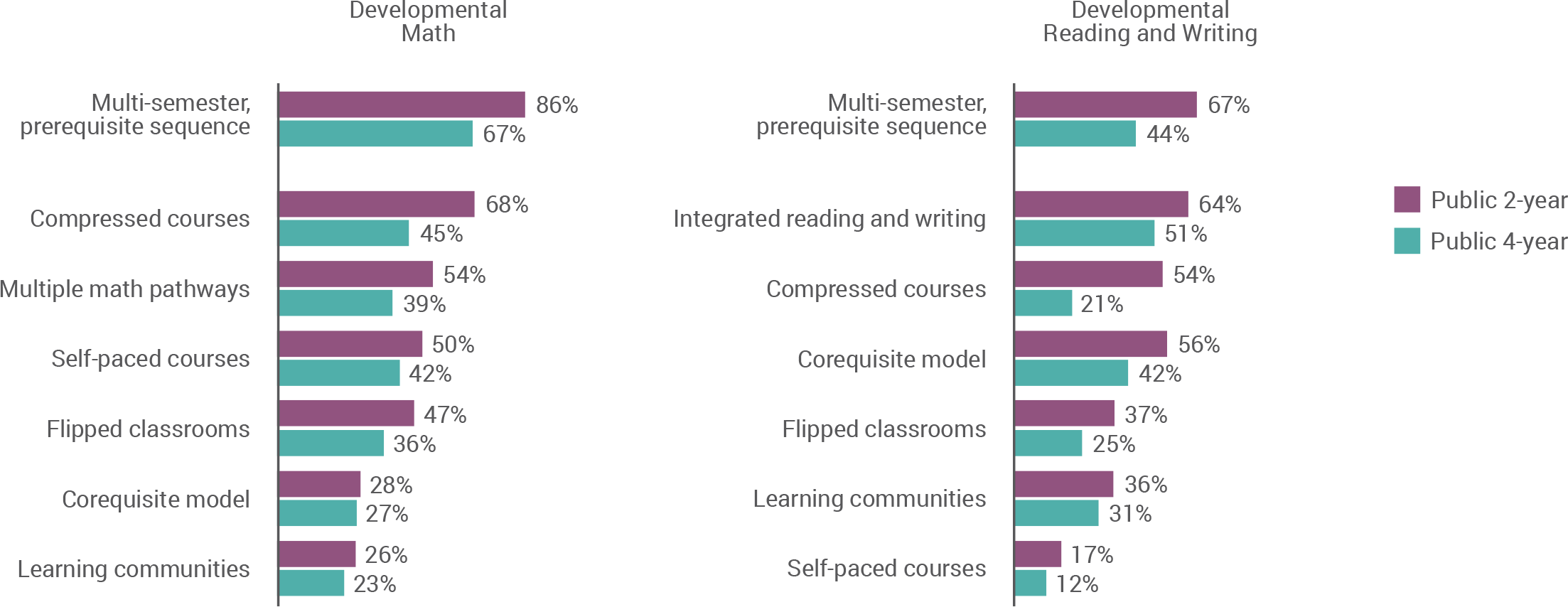

Multisemester prerequisite course sequences continue to be one of the primary ways colleges provide developmental education, though many public colleges are also experimenting with different approaches to instruct and support these students.

Over 40% of public two-year and four-year colleges offer developmental courses as multisemester prerequisite sequences. However, other instructional approaches are being implemented in more than half of community colleges and a significant proportion of four-year colleges. The most prevalent are integrated reading and writing, multiple math pathways, corequisite, and compressed courses. However, as of 2016, most of these reforms have not been scaled. Few colleges offer these reforms in half or more of all their developmental education sections.

Instructional Approaches to Developmental Education Among Public Colleges, Academic Year 2015–16

Many colleges also have students identified as in need of developmental education using academic and nonacademic supports. More than two thirds of public colleges have at least some of these students working with tutors or supplemental instructors and participating in student success courses or working with success coaches. A majority also have at least some students with math needs using computer-based learning sessions or prematriculation programs or boot camps. More community colleges reported having students using these support services than public four-year colleges.

Many factors drive colleges’ practices in developmental education, but it’s not yet clear which factors are most important.

The report uses survey and interview data to explore the interplay between factors driving developmental education policy within institutions. Most colleges reported that a variety of factors influence their efforts to improve developmental education, including input from faculty, research conducted by the institution, the availability of resources, practices at other colleges, research conducted elsewhere, and state policies. State policy was cited less frequently than other factors, but an analysis of practices in three states with mandated policies around developmental education suggests that state policy may have a more important influence in some states than others.

There is still more to learn about developmental education in private colleges.

Few private two-year colleges and private for-profit four-year colleges responded to the survey (despite multiple contact attempts by CAPR researchers), and as a result, CAPR removed them from the analysis. Given that private colleges serve a large proportion of low-income students, it remains essential to continue building knowledge about the developmental education practices these colleges are implementing and their effectiveness.

This report sheds light on how rapidly the field of developmental education is changing—a trend that likely has only grown since the CAPR survey was disseminated, as more and more states are mandating changes to colleges’ developmental education practices. However, despite many colleges’ experimentation, a large group of colleges are not making changes—or at least to the degree policymakers might hope. This underscores the urgency in understanding what reforms may be most effective and how they can be more widely implemented among the nation’s colleges.

For more information about the study, its methodology, and its implications for future research, see The Changing Landscape of Developmental Education Practices: Findings from a National Survey and Interviews with Postsecondary Institutions.

| Dominique Dukes is a research assistant at MDRC and a coauthor of the report. |